PrestaShop in 2019 and beyond, part 3: The Future Architecture

aka Point B – Where we are going

This is the third in a series of articles we introduced earlier this year, that aims to describe where we are, where we are going, and some ideas on how we’ll get there.

The Future Architecture

(or “Point B – Where we are going”)

In the first part of the series, we described what the current architecture looks like. Then, the second part covered the fundamental things that were wrong with it. In this part, we’ll discuss what we think the future should look like for PrestaShop.

This is an article that I’ve been meaning to write for what now seems ages, and it’s essentially the reason behind this whole series. If you attended one of my workshops at PrestaShop events, you probably have a general idea about what I’m going to talk about now, as I have already provided some exclusive previews there. But even if that’s your case, I suggest reading this article, as it brings further insights in what we think will be the future of PrestaShop, and why.

Over two years coming

As discussed in the previous articles, one of my first tasks when I arrived at PrestaShop in 2017 was work on a technical vision. I had immediately noticed that PrestaShop had fallen prey of the many pitfalls that projects their age usually show: custom framework, monolithic architecture, static classes, spaghetti code, shared state, and so on. Nothing special so far.

What really struck me was the amount of inconsistencies I found: coding style, duplicate subsystems, prices being calculated with tax then re-calculated to remove tax, character set conversions that no one was able to explain—even legacy controllers, which look like they were designed to execute a single action, had been subverted into incongruence in order to handle multiple actions. It really looked its age: layer over layer of changes made by a thousand hands shuffling things around over the course of a decade, without really understanding why things worked that way nor what the original intent was. Some subsystems had even been replaced by new ones without anyone being able to explain why or how they were supposed to work. Madness!

As a code archeologist, I can’t say I was surprised. After all, where was the master plan, the big picture, any guidance to return strayed developers back to the right path? I was unable to find any trace of such thing.

Software engineering can be easily assimilated to traditional engineering. Imagine a house being built with no plan, without a precise idea of what you want it to look like in the end or how many rooms it’s supposed to have. Now, picture an architect leading a construction site and going like this: “Okay guys, just pile up some bricks here and add some columns there and we’ll see where it takes us.” It sounds ludicrous, right? So why would it be acceptable to lead a development as complex as PrestaShop like that?

Of course, that’s how the software world works: move fast, break things. If it is perfect when you release it, you probably released it too late. We know PrestaShop isn’t perfect, but it did meet user’s needs, and you don’t reach the success PrestaShop has if you don’t answer real business needs.

However, if you want to get somewhere, anywhere, the first thing you have to do is decide where you want to go. It’s only after that that you can start thinking on how you’ll get there.

So we started working on that.

When I first started talking about a new architecture during my first presentation before agencies at PrestaShop’s Paris HQ back in 2017, attendants were rolling their eyes. “Seriously?”, they said, “Are you seriously changing everything again? We’re already struggling with 1.7 and now we’ll have to spend money rebuilding our themes and modules again?”.

I already knew by then that an architecture change isn’t done overnight—especially for a development platform. So I reassured them by saying that it was our long-term vision and that they didn’t have to worry about that right now, and that was the end of it.

But even today, four years after announcing 1.7 would be Symfony-based, many people are convinced that the Symfony migration was a waste of time and money, and that PrestaShop just did it to “force people into buying new modules”. Some think that Symfony is a solution looking for a problem to fix, a problem that didn’t exist in the first place. I hope that after having read the previous two parts, you already understand that we’re not doing it, as someone once put it, “just because we enjoy beautiful code” (even if we, as most developers, actually do enjoy beautiful code). There are many issues to fix, yes, I know. But migrating to Symfony is a way of progressively giving more sense to PrestaShop’s code, using modern tools, and improve its quality through incremental refactoring.

Similarly, since last year we have been making architecture choices that may have seemed arbitrary or incomprehensible to some. “Why are you making it so needlessly complicated?”, they said. Rest assured, there is a good reason. Each choice we make answers to a specific problem in the context of a bigger long-term vision. We just needed time to put this reasoning into words (or should I say, articles), so that everyone understands not just what we are planning to do, but more importantly, why we are leading the project in this direction.

What drives a new architecture?

When we began thinking about a new architecture, we started with a simple exercise: if we had to build PrestaShop again, what would its architecture look like?

A solution for every problem

Our first job was trying to understand what our current problems were and where they were coming from–this is what the previous articles were about. Once we knew what was dragging us back, we were able to start looking for answers.

A new architecture should provide an answer to each one of PrestaShop’s main structural problems.

Interaction delays

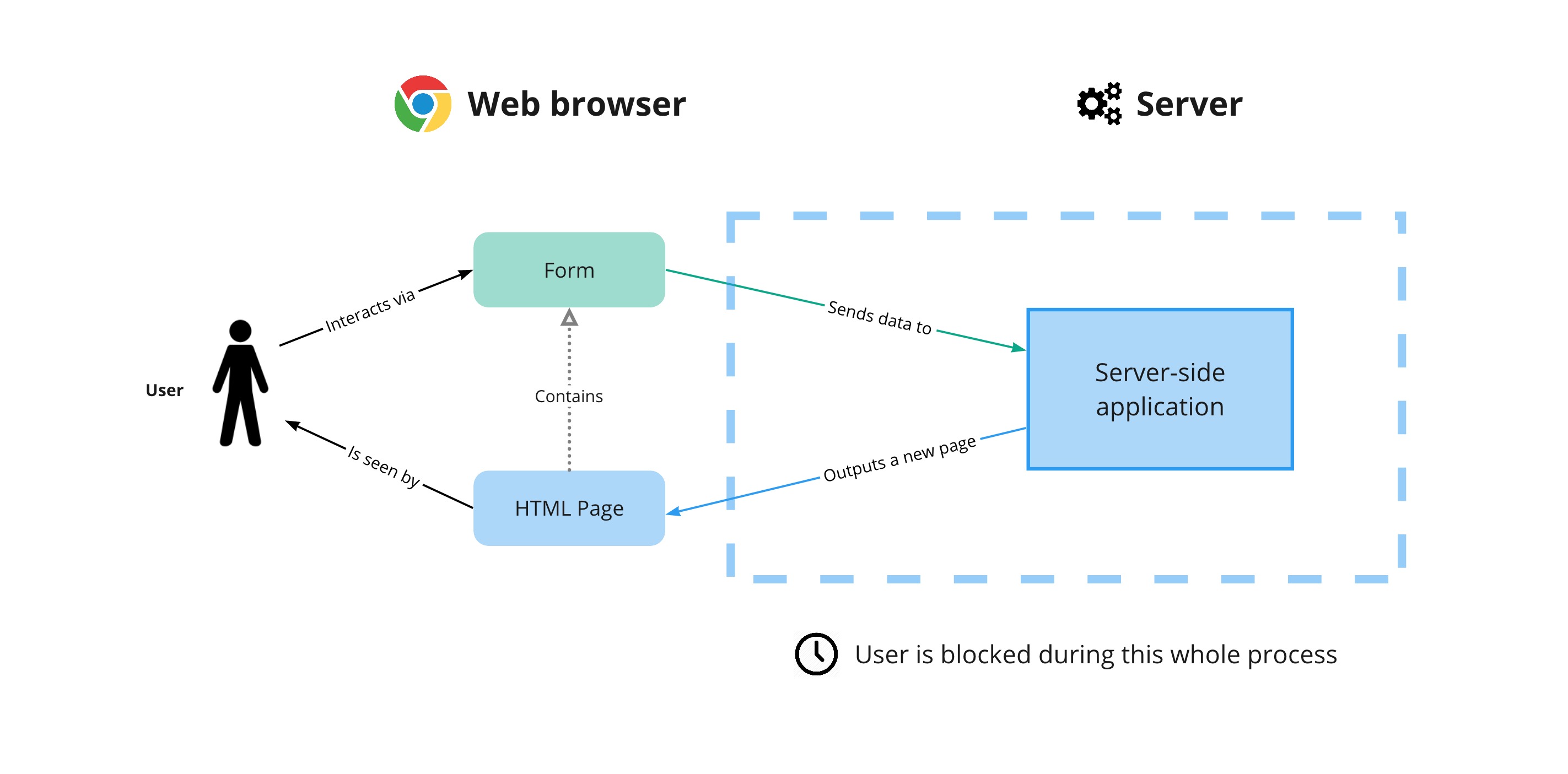

The interactive web, since its dawn in the nineties, has been based on a process where the user opens an HTML page containing a form, fills it out and sends it to the server, who takes the form data, processes it, stores it in a database, and produces a new HTML and form which is sent back to the user, restarting the cycle. One of the problems of this pattern is that once the user performs an action, they are blocked and must wait for the whole page to reload before being able to interact with the page again.

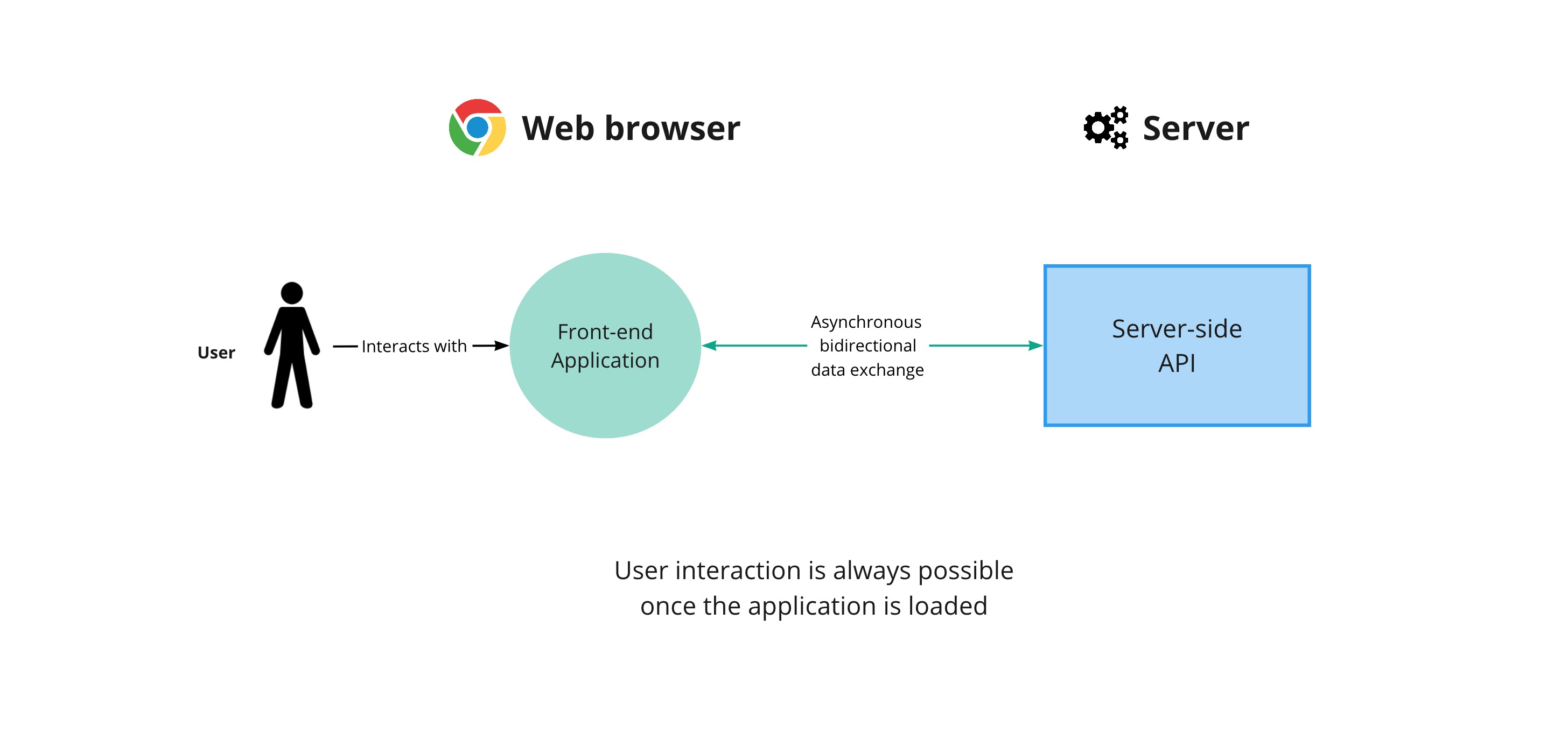

The wait-for-reload-between-interactions problem has been basically fixed for a long time now. Modern architectures are usually based on front-end, Javascript-based applications that are loaded once and run in the browser. In this kinds of apps, all data exchange between the front end app and the server is performed asynchronously (ie. in a non-blocking manner) through XmlHttpRequests (also known as Ajax) or using Web Sockets. This brings enhanced responsiveness to the user interface, allowing the user to continue interacting with the application while data exchange is performed.

Meanwhile, on the server side, information is served and received through an API (Rest or GraphQL, for example) in a format designed for data transport, like XML or JSON. Outputting data in a structured format further enhances responsiveness, thanks to a reduced volume of data traveling between browser and server. In addition, by separating data from presentation, both the presentation and the data themselves can be processed more easily and efficiently.

Data-centric design

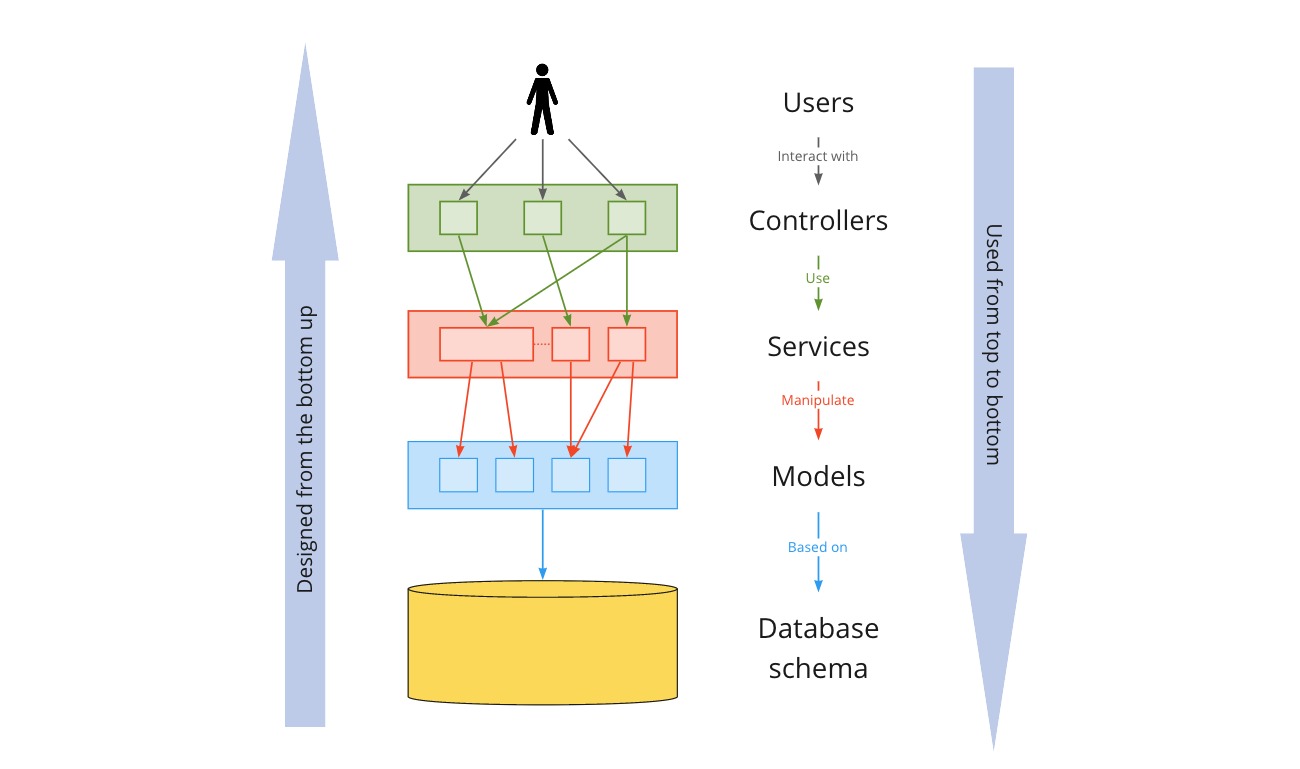

PrestaShop was designed in a traditional data-centric way. In this kind of design, systems are built “from the ground up”: business subjects (like Users, Products, etc) are modeled as simple objects, usually following the database schema, and then their behavior is given by one or many abstraction layers placed on top of that model. This design encourages thinking about every action in terms of data (as opposed to state), because in the end, all high level services are actually built on top of CRUD actions performed on thin, behaviorless models that are placed at the bottom and support the whole structure.

The problems associated with this architecture have been explained in previous article: upper layers are tightly coupled to models, because they are based on thin models which by definition (since they have no behavior) need to be micro-managed. This makes iterative enhancements harder to implement because since each layer either micro-manages its lower layer or is closely dependent on its implementation, any change in an upper layer usually requires a change in lower layers as well so that it provides the “buttons and levers” that the upper layer needs.

As a consequence, this kind of architecture is more often than not coupled with a never ending stream of “oops, this design didn’t account for that special case” kind of issues, that pushes developers to create ad-hoc solutions, further aggravating the situation because of crisscrossing dependencies, responsibility dilution and increased complexity–all resulting in a codebase that is harder to maintain and more bug-prone.

All this is not new. As systems evolve and grow bigger, one of the hardest problems in software engineering is how to handle this inevitably increasing complexity. Eric Evans’s Domain-Driven Design (“DDD” for short), a software design approach that has been gaining popularity recently, attempts to tackle this problem by choosing a dramatically different angle: it advocates for focusing on the core domain (ie. “business logic”–what the application does) and ubiquitous language (ie. “business language”, or expressiveness).

In my interpretation, this design strategy is opposed to data-centric designs, where models reflect database elements and services manipulate their data. Instead, DDD focuses on modeling business objects and their interactions, based on user’s intent and what make sense from a business, real-world-case scenarii; it gives models behavior that responds to state transitions that make sense from a business standpoint.

This means that implementations are built to closely represent business needs, instead of being based on technical representations of the database model. In other words, design should be done from top to bottom, instead of from the ground up, so that lower layers implement the needs of upper layers instead of providing their basis.

Let’s try an example.

Scenario: A as User, I want to update the price, tax excluded, of a Product.

In a data-centric design way, here’s how it would typically be done (note: this doesn’t reflect how it’s done in PrestaShop):

<?php

// this returns a thin model, which is basically an data bag straight from DB

$product = $productRepository->getById($productId);

if (!$product) {

throw InvalidArgumentException("Product doesn't exist");

}

$newPrice = $_GET['price']; // 123.45

if ($newPrice < 0) {

throw InvalidArgumentException("Price cannot be negative");

}

$priceCurrency = $_GET['currency']; // USD

// ensure price is in the shop's currency

if ($priceCurrency != $this->getDefaultCurrency()) {

$newPrice = CurrencyConverter::convert($newPrice, $this->getDefaultCurrency, $priceCurrency);

}

// update price

$product->price = $newPrice;

// don't forget to save...

$productRepository->save($product);

// don't forget to update specific price cache!

SpecificPriceManager::updatePrices($productId, /*... other things*/);

And here in DDD:

<?php

// we don't care where or how it's stored

// throws a typed exception if not found

$product = $productRepository->getByProductId($productId);

// this returns an instance of Price value object

// and throws a typed exception if the price or currency is not valid

$newPrice = new Price($_GET['price'], $_GET['currency']);

// this is not a setter, it's a state transition

$product->updatePriceWithoutTax($newPrice);

As you can see, the consumer code doesn’t have a clue on how the action is performed. It just knows that it has to call “updatePriceWithoutTax” and pass along the new price. Code is much more readable because it shows intent and nothing else. Consumers don’t need to know how the action is performed, they just need to prepare whatever requirements are needed and call one line of code. The implementation is delegated and can be adapted and reimplemented as needed.

Of course, this is a very simplistic explanation, and there are many, many more things to say about DDD. If you’re interested in learning more about this design approach, read this quick 5-minute article about the fundamentals of DDD.

Global state

Here is a fun story about shared state. The historical implementation of order creation in PrestaShop required a Cart instance being set available in the global Context, because it was used by multiple services that depended on it implicitly through Context::getContext(). This means that when a merchant wanted to create an order from the Back Office (where there’s obviously no cart) PrestaShop needed to set up a global Cart in the Context, as if they were buying from the Front Office.

This should never, ever be necessary. Static classes are evil because they cannot be injected, and singletons are the worst offender because by definition they behave like global variables. As explained before, global state is a Very Bad Thing because it produces “invisible strings” that tie components that would seem otherwise independent, in such a way that any change in global state can produce unintended, unpredictable side-effects in another part of the system you weren’t even aware of (like if when you closed the door it made a window open itself in the opposite side of the room). This is why all dependencies should be injected, and classes should either be stateless or immutable.

The same can be said about in-memory static cache, which is another classic performance hack that ends up producing hair-pulling bugs. This technique is used to store data in cache across multiple calls to the same method, even if those method calls are performed on different instances of the same class. More often than not, this points to a design flaw and can be avoided by either refactoring or injecting cache providers (which also provide more convenient and powerful storage and invalidation options).

No clearly-defined API / Everything is public

One of the biggest problems in PrestaShop is that since it has no clearly-defined public API, everything is de facto considered to belong to it.

The meanest part of this issue is the overrides system, which allows to redefine any public and protected method in any legacy class. The problem with it is that by violating the Open/Closed principle, it prevents the Core from evolving and from ensuring that its internal state is correct at all times.

Classes that cannot be overridden also suffer from this problem. Even if they were originally meant for internal use, the statu quo indicates that as soon as they exist and are released, somebody could be using them, and therefore, any change in their behavior or interface is considered a breaking change.

This problem can be solved by clearly stating what belongs to the public API and what does not.

Driving forces

Designing a new architecture is not just about solving problems. It also has to answer to a certain philosophy, a way of seeing things that drives our design choices and settles our priorities. What’s important for us and non-negotiable? What are the trade-offs that we are willing to accept?

It has to be coherent

Coherence should be of utmost importance in a new architecture. Not only there should be one and only one way to perform a given task, but it should also be intuitive both in its implementation as well as its discoverability (i.e. avoid the classic question of “Where’s the class that handles that feature again?”).

In addition, a well-designed architecture should be internally coherent and resilient to errors. The Core should therefore enforce coherency in its internal state and reject any possibility of incoherent input, by design. This means, among other things, strict typing and typed exceptions.

It has to be solid, extensible and intuitive

PrestaShop is a platform for building e-commerce websites, so obviously developers will need to be able to extend its behavior in order to add specific features like payment and delivery providers, ERP connectors and so on.

For that, developers should have a powerful, stable, and well-documented toolset at their disposal. This includes extension points, well-defined channels for communicating with the Core, and a set of predefined modular components that encourage reusability and coherence across the ecosystem.

In order to enforce systemwide coherence, the Core should be at the center of all state changes. Similarly, system state micro-management should be strongly discouraged.

It has to be decoupled

The server-side Core interface needs to become fully independent from its clients, whether it is the front-end user interface or extensions, both in the Front Office and in the Back Office.

PrestaShop is complex all on its own, but it’s also a development platform. In order to be flexible, it has to be made out of a large number of small, independent components, instead of the other way around.

It cannot be everything at once

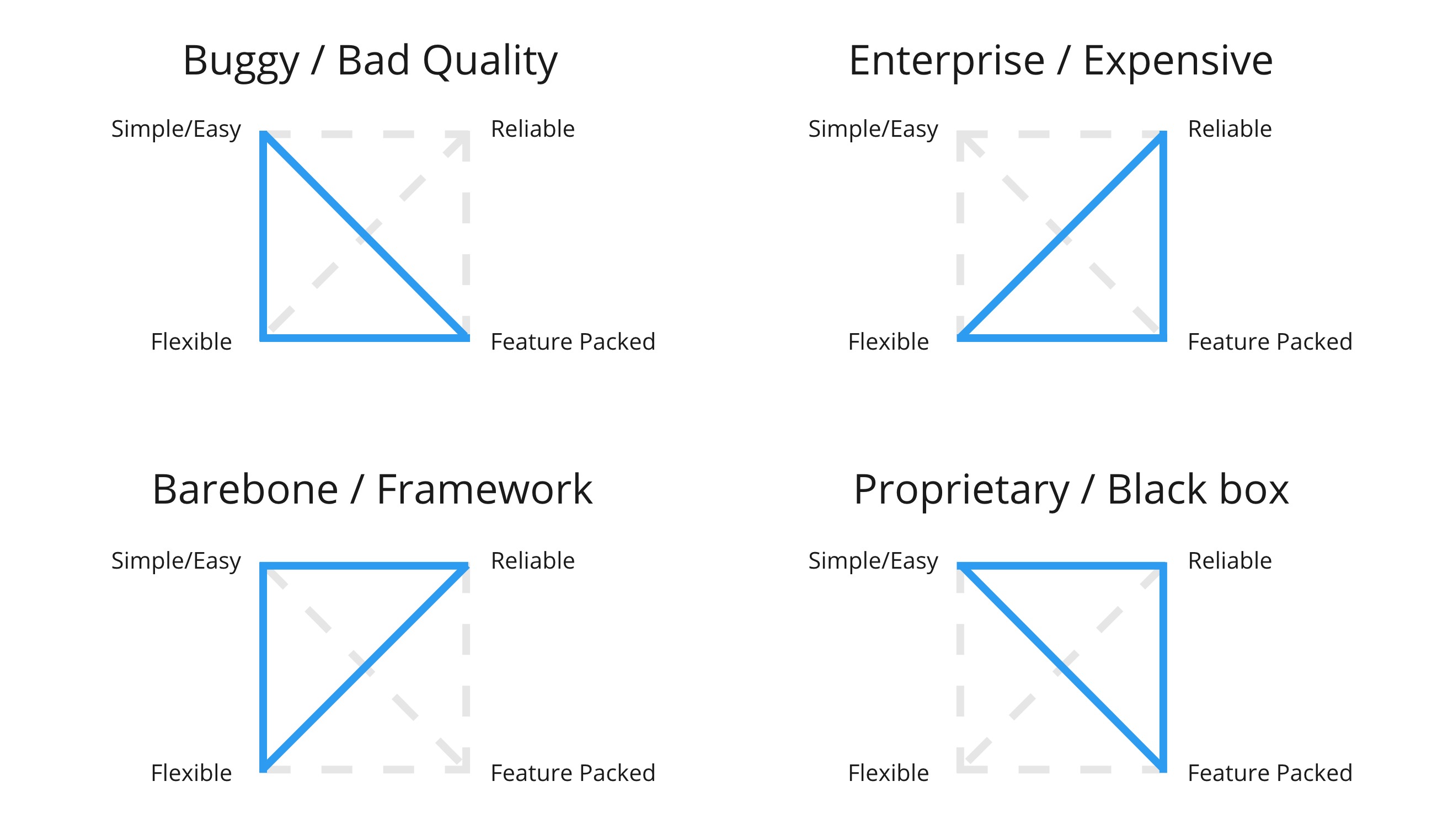

I believe that software quality can be measured in 4 key dimensions:

- Simplicity / Ease of use: How easy it is to work with it

- Flexibility: How customizable it is, how well can it adapt or be adapted to your needs

- Reliability: How stable it is, how prone it is to behave unexpectedly or perform below expectations

- Features: How powerful it is, how many things it can do

An ideal software should be good in all four. But let’s be honest: in the real world, it’s not possible to excel in everything at once. In order to really perform at a high level, some trade-offs need to be made, and it usually means focusing on a smaller number of things.

Much the same as the “Fast-Good-Cheap, pick two” problem, in my opinion, software can only be realistically optimized for three of these quality axes at a time, and one must always be sacrificed in the interest of the others. Here’s a graphical representation:

If we are forced to choose between one of these archetypes, which one would we be rather be? Not buggy, that’s for sure. Not proprietary either, because PrestaShop is an open source platform. We have to choose between having very few features but do them really well, or have many features at the cost of a steeper learning curve.

Our proposal for a future Architecture

Based on the everything that we stated before, here’s what we came up with:

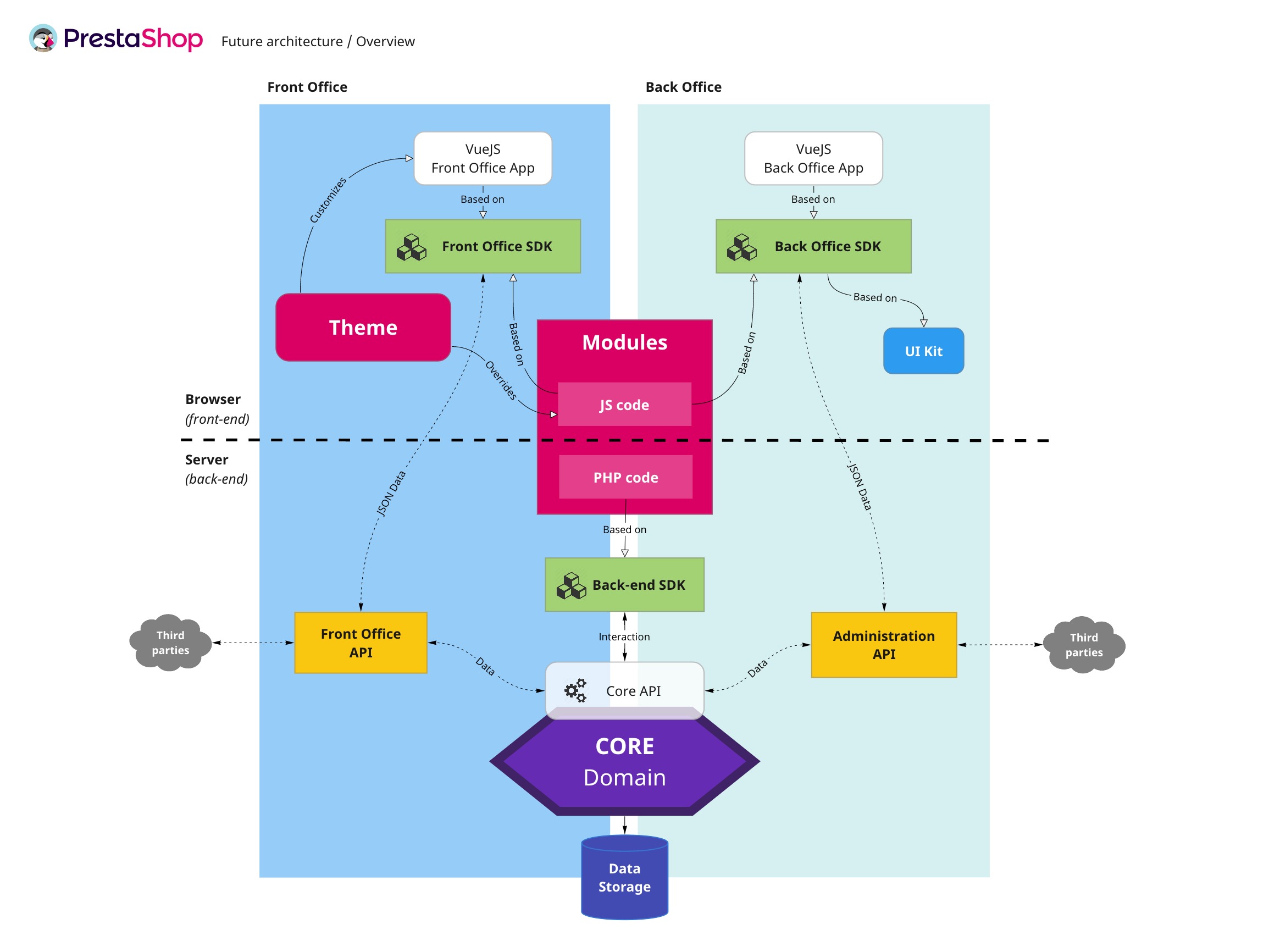

The future architecture is based on 5 key elements:

- Core Domain

- Front-end applications

- Contracts and Tools (SDKs)

- APIs

- Extensions

The Core sits in the back-end and is at the center of it all. It accounts for all the business needs and use cases that PrestaShop is capable of doing (managing products, shopping carts, orders, etc.). The Core is domain-oriented, meaning that it is built around business use cases, expressed in an ubiquitous language. The Core is also master of its own Domain; in order to let it be the guardian of system-wide coherence, it has to be isolated from other services and be the only one capable of performing state transitions. Other services can only interact with the Core through well-defined interfaces, that we call the Core API. Incidentally, this also means that Core behavior can be extended, not modified, by other services–or at least not in a way that it puts system coherence at risk. In addition, the Core is designed to be easily testable and is covered by automated tests.

In the future architecture, the Back Office (BO) and the Front Office (FO) are independent front-end applications, each one running entirely on the browser. They are fully component-based (our framework of choice is VueJs), and built using separate toolsets called Software Development Kits (SDKs): one for the FO, one for the BO. These SDKs would not only include reusable components, but also bidirectional communication channels based on stable contracts, both within the front-end application (events) as well as with the back-end (through APIs). The BO SDK also integrates the UI Kit, which provides an uniform style for the whole Back Office.

The Core and FO/BO applications communicate through two separate APIs, namely the FO API and the BO API. These APIs serve two distinct purposes: while the FO API is public and designed to serve customer-facing applications (e.g. the FO application, but also other custom clients, like mobile apps or Point of Sales in physical stores), the BO API is protected by access rights (much like the current Web services) and is meant to power the BO application, as well as third party integrations like ERPs. In order to maximize forward compatibility, APIs and SDKs are versioned.

Of course, the future architecture supports Extensions, which can be placed all over the system. Modules can hook on to existing features or add new ones, either on the front-end applications as well as in the back-end (for data processing). On the front-end, Modules are based on the FO/BO SDKs, whereas server-side they are built on top of the Back-end SDK. While Front-end SDKs allow Modules to interact with front-end applications and retrieve data through PrestaShop’s APIs, the Back-end SDK provides access to the Core API, which allows Modules to query data directly from the Core, perform state transitions, extend existing API endpoints and even create new ones. In order to ensure system stability, Extensions can only interact with PrestaShop through APIs and SDKs.

Finally, Themes are a particular kind of extension that sits on top of the front-end application and that defines the layout and style for components provided by the application, FO SDK, and any installed Modules.

Why it’s better

We believe that the future architecture is the best long-term solution to the problems that we discussed above and in the previous article.

Separate applications with clearly-defined APIs and SDKs will provide many benefits:

-

Increased flexibility. Making the user interface fully independent from data processing will allow developers to better fashion PrestaShop into whatever solution they need: like a radically different Front Office, or choosing to power a mobile app while leaving just a landing page for the web interface… all without having to change the Core.

-

Better compatibility. Since the Core and front-end applications can evolve independently and rely only on well-defined common contracts, it’s much easier to introduce features without introducing breaking changes. In addition, since APIs can be versioned and maintained in parallel, backwards incompatible changes can be introduced on an opt-in basis.

-

Enhanced developer experience. Well-defined, well-documented contracts makes it much easier for developers to discover how to retrieve information and how to perform the actions they need. Reusable components provide a unified experience and accelerate development.

-

Simpler, more powerful extensions. It’s much easier to extend independent simple elements than closely coupled, complex systems. For example, it’s much more straightforward to add a button on a page using Javascript than by modifying HTML markup through fixed hooks. Similarly, it’s easier to enrich data by post-processing a JSON-formatted API output than to hook into deeply-nested services that are hard to understand.

A Core Domain that’s open for extension and closed for modification will also be beneficial:

-

More stable. The Core can be better at ensuring system consistency because it disallows third parties from side-stepping its checks. Similarly, having only one way of performing a given action reduces overall code complexity, which according to Microsoft Research is one of the top bug predictors.

-

More flexible. Cutting the Core away from external interference means liberating it from most of its interface contracts. Thanks to that, refactoring can be performed without introducing breaking changes, and the Core is free to evolve more freely and quickly.

A vision, not a milestone

This architecture is not meant to be a project in itself with a beginning and an end. It’s not meant to be PrestaShop v2–it would have to be rewritten from scratch, and that would be a terrible idea.

Conversely, this is meant as a long-term vision that will guide the project’s development for many releases to come. An objective that we intend to reach sooner or later, yes, but with no fixed date. And even though this whole idea may seem distant and diffuse right now, I’m sure it will become clearer and clearer as we advance towards it. In the meantime, I’m convinced that it will help the project move forward in a more precise and determined way.

As long as we make sure that every decision we make brings PrestaShop one step closer to this vision, I have no doubt that we will get there.

In the next and final article of this series, we will discuss some concrete ideas on how we can start moving towards the future architecture, and how some of them are already being implemented in PrestaShop.

About the series

In case you forgot, here are the topics that will be covered during this series:

- The Current Architecture (or “Point A – Where we are”)

- Pain Points (or “What needs to be improved”)

- The Future Architecture (or “Point B – Where we are going”)

- Connecting the dots (or “Some ideas on how we’ll get there”)