PrestaShop in 2019 and beyond, part 1: The current architecture

aka point A – Where we are

This is the first in a series of articles we introduced a couple days ago, that aims at describing where we are, where we are going, and some ideas on how we’ll get there.

As pointed out in the introduction article, the first step to be able to map a path into the future is to understand where you stand currently. In this article, we’ll try and describe the current architecture of PrestaShop.

The Current Architecture

(or “Point A – Where We Are”)

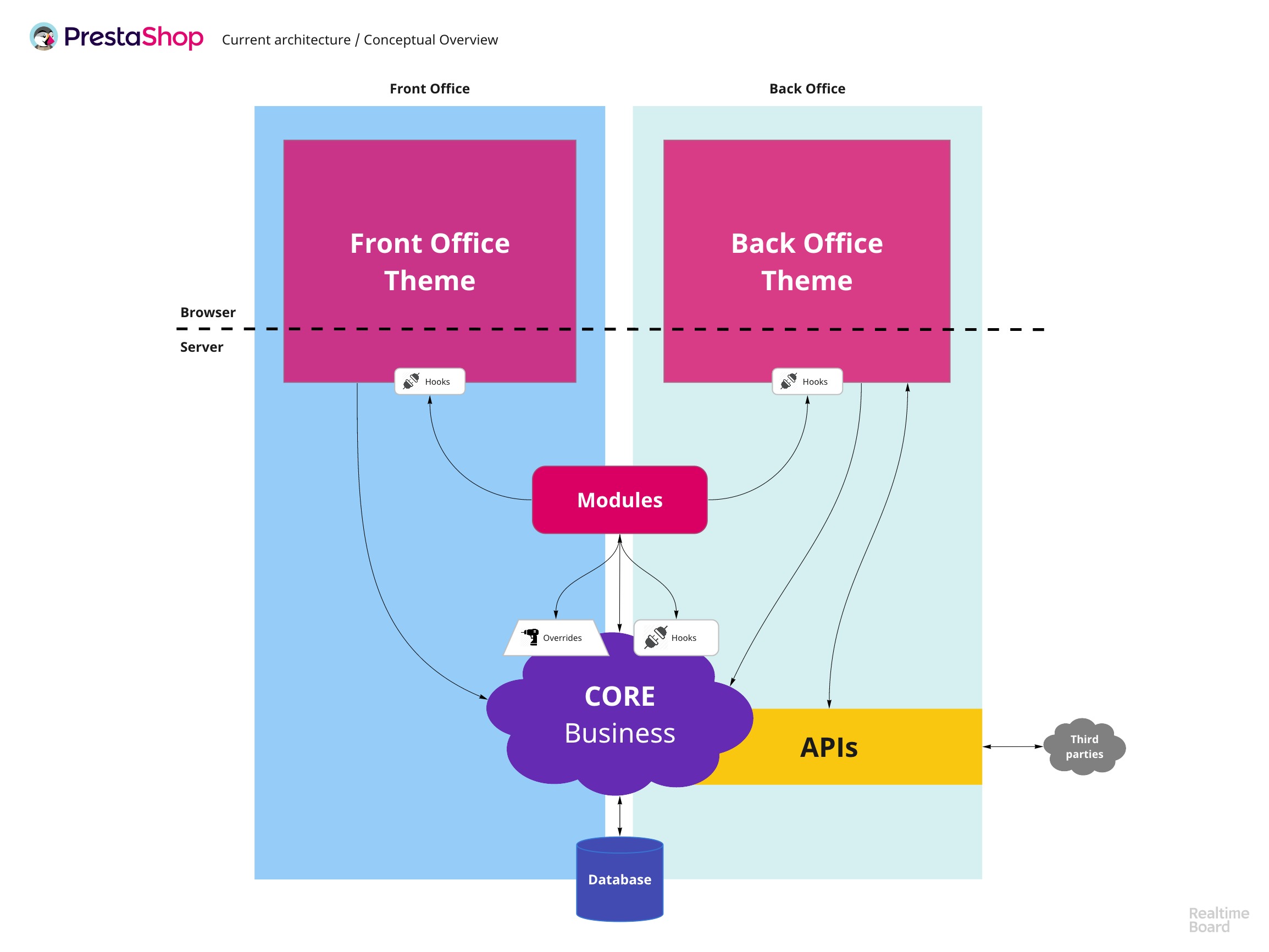

Here’s an overview of what PrestaShop 1.7 looks like as of early 2019.

(Figure 1: Basic overview of PrestaShop 1.7’s architecture, early 2019)

(Figure 1: Basic overview of PrestaShop 1.7’s architecture, early 2019)

PrestaShop’s architecture can be separated in two main logical sections:

- The Front Office (or FO) – the public-facing site of a shop,

- The Back Office (or BO) – where merchants manage their shop.

In Figure 1, this is represented by two big, blue(ish) columns.

Each of these sections can be themselves separated in two parts, which are common to all web applications:

- The front-end – the part that essentially runs in the browser,

- The back-end – which runs in the server.

In Figure 1, this separation is represented by a horizontal division with a dotted line, where “Browser” represents the front-end, and “Server” the back-end.

Overview

If we analyze how the back-end is structured, we can find some common elements to BO and FO:

- Database

- Core Business

- Modules

Like most web applications of this kind, PrestaShop is heavily Database-driven. That’s where the Single Source of Truth is found. This means that all data is stored there, regardless of whether it’s used in the BO or FO.

In Figure 1, the database is placed a little outside the diagram to point out to the fact that it’s a system of its own that could be on a separate server, in a cluster, etc.

The purple cloud depicted above the Database is what we call Core Business. It’s the big ensemble of code that manages what makes PrestaShop PrestaShop, also referred as “business logic”. It includes controllers, helper classes, and such. We will cover this aspect in more detail further down this article.

Then, there’s Modules. Modules allow to customize PrestaShop in many ways. They interact with the Core either by hooking into extension points (which are placed throughout the code) or by replacing core components with their own (using either the legacy Overrides system or symfony service definitions).

While in this diagram we have placed Modules on the Back-end side of things, they can actually have an impact on Front-end as well. We will address that when discussing modules.

PrestaShop has mainly two ways of presenting information to the browser: HTML pages and Structured data (XML or JSON).

Controllers will mainly output HTML pages. The structure of those pages is defined by a theme, which transforms controller-provided data into HTML. This is true both for the FO and BO.

In Figure 1, themes are depicted by pink(ish) columns overlapping both the front-end and the back-end.

PrestaShop 1.7 supports third-party themes in FO, but not in BO. Confusing as it may seem, there are two BO themes, called “default theme” and “new theme”. Don’t worry, this will be explained in the themes section.

PrestaShop has two API interfaces:

- BO API – used to serve information to VueJS-based pages (currently Translations and Stock management),

- Web services – used to integrate 3rd party services.

While Web services can output XML or JSON data, the BO API is JSON-only.

On the front-side, things vary a lot depending on the theme. We will cover this when we address themes.

Now that we have a general idea of how things work, let’s dive a little deeper into that purple cloud…

The Core Business stack

While controllers will be different in BO and FO, pretty much all of PrestaShop’s PHP code is shared between those two environments. This code is split in four logical subsystems:

- Legacy code – located in

/classesand/controllers - Adapter code – located in

/src/Adapter - Core code – located in

/src/Core - Symfony code (or “PrestaShop Bundle”) – located in

/src/PrestaShopBundle

To explain this structure, let’s look back a little.

Up until 1.6.0, all shared code lived in the classes directory. One of the main problems with the legacy architecture is that classes are both static and too big. Since refactoring all legacy classes would take a very long time, during the development of 1.6.1 it was decided to separate legacy code from new, loosely coupled code.

This decision aimed at gradually producing a cleaner codebase without introducing breaking changes, thus giving module developers time to adapt their modules.

Recap: Why it’s important to have uncoupled code

Code coupling is the degree of interdependency of two modules. As coupling increases, the system starts exhibiting some common problems:

- Changing something in A forces you to change something in B, then C, then D…

- Change something in D may produce unwanted, unforeseen effects in A, resulting in bugs.

- It’s harder to adapt or reuse code, because paths have been pre-established (referred to as “hard coding”).

- It’s harder to test modules independently from each other.

Uncoupling code via careful design using SOLID principles allows to tackle those issues.

Following this, the structure was split in three pieces:

- Legacy code – which remained as it was

- Core classes – new, clean code

- Adapter classes – a bridge to legacy classes, allowing to avoid hidden legacy dependencies in Core code

During early development of 1.7, with the introduction of Symfony framework, a fourth, Symfony-based subsystem was added: PrestaShopBundle. While the rest of the code is pretty much framework agnostic, the PrestaShopBundle is a Symfony bundle and therefore contains Symfony-specific functionality.

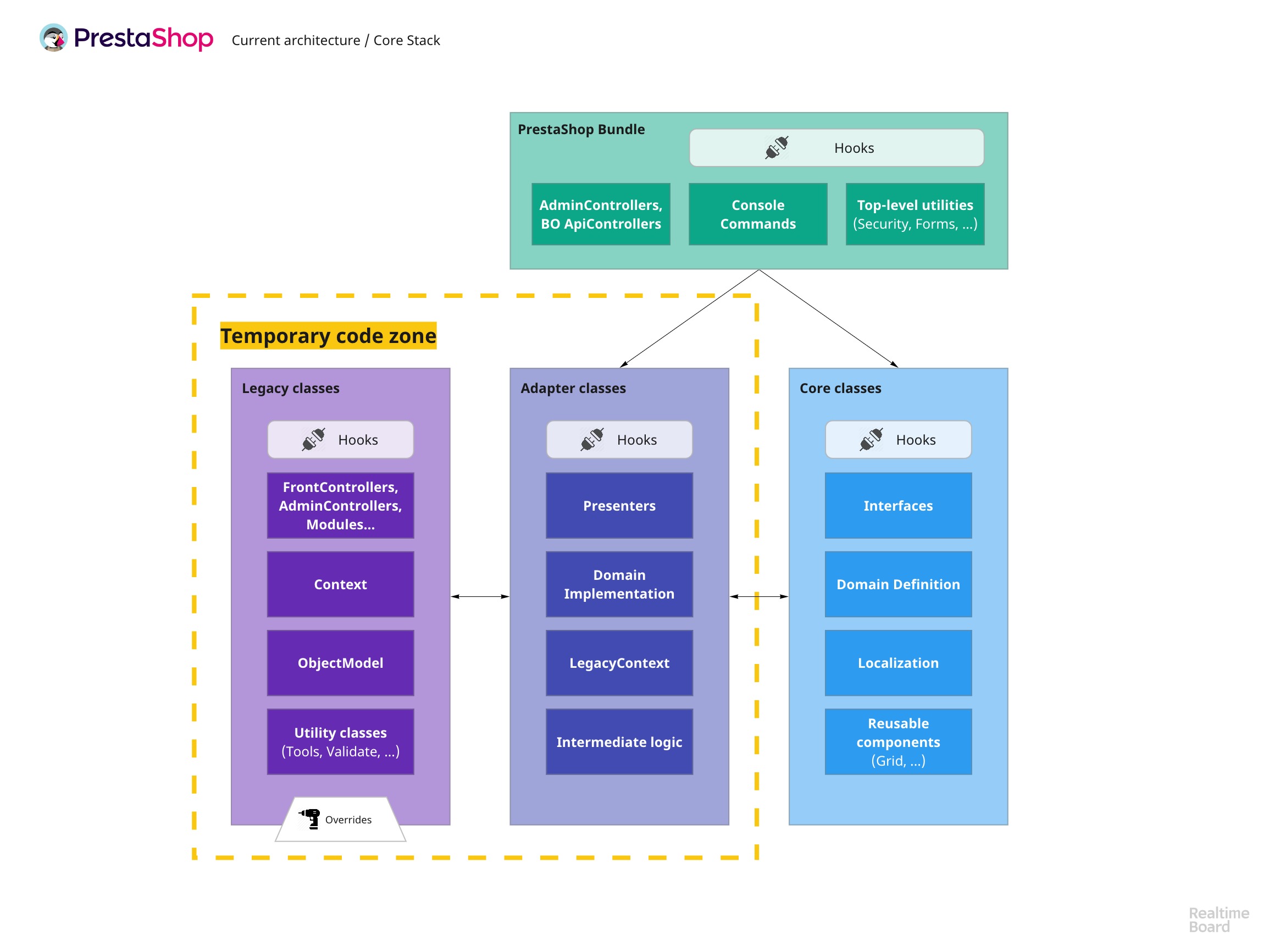

Here’s how it stacks out now:

(Figure 2: The core business stack)

(Figure 2: The core business stack)

In Figure 2, we can appreciate the four subsystems described above.

If you’re thinking that this separation is excessively complex, you are right! But this transition phase is necessary to allow us to move forward progressively. Here’s how.

Notice the dotted yellow zone labeled temporary code? Code within that yellow zone is, you guessed it, temporary. This means that that code will sooner or later be moved to the Core or PrestaShop Bundle stack, and once that zone it’s empty, it will be deleted. Of course, such a change won’t be done in a minor version, so you can expect these four stacks to be present for the whole lifetime of 1.7.

If you look closely at the relationships between each stack, you’ll see that code outside the temporary code zone does not interact directly with legacy classes. As explained before, the Adapter layer sits between the Legacy and the “new” code to ease up the transition of code from the Legacy stack to the Core stack.

How does that work?

Whenever a Core (or PrestaShopBundle) class needs something provided by a Legacy class, instead of using the Legacy class directly, it delegates that task to an Adapter, which itself uses the Legacy class (see Adapter pattern).

Here’s where it gets interesting. Generally, these Adapters implement an interface declared in Core (even though it hasn’t always been the case, new classes do). Making consumers of that Adapter depend on the interface instead of the Adapter class itself (see Dependency Inversion principle) will allow to reimplement Adapter classes in Core progressively, without having to change the existing code that depends on them.

Why not use the Legacy class directly?

For starters, most legacy classes are static, and since by definition they cannot be injected, it would result in coupled, untestable code. In addition, the ones that are not static generally still have too many responsibilities (see Single responsibility principle) and/or too many public methods or properties (see Open/closed principle), so they cannot be made to implement a proper interface.

As a side note, you may have noticed that all stacks contain Hooks as extension points, but only the Legacy stack has overrides. We’ll address that in the next part in this series (no spoiling!).

Controllers

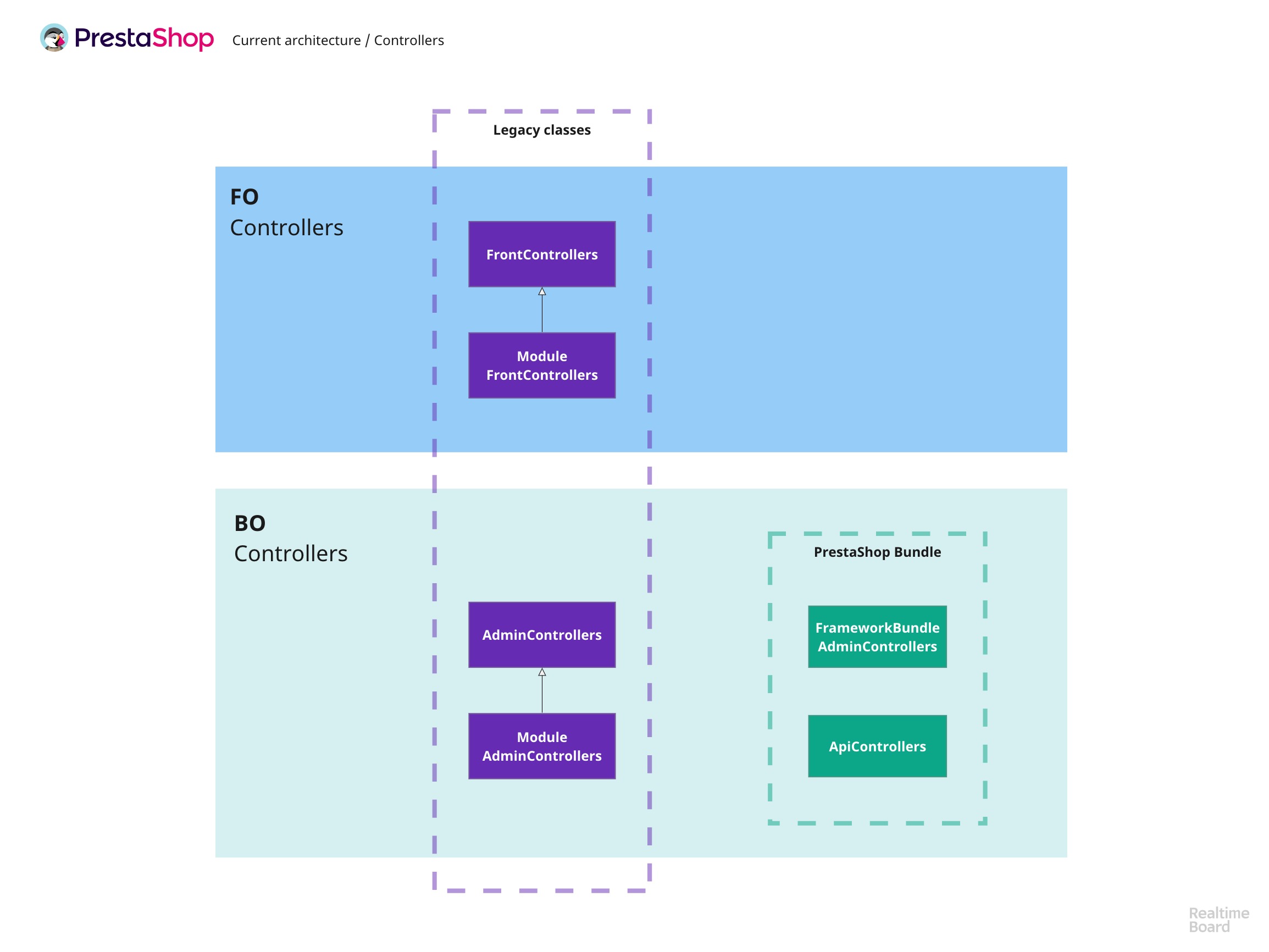

PrestaShop is based on the MVC pattern, where Controllers are in charge of handling requests and returning responses, ideally delegating the hard work on dedicated services.

Controllers are divided in two big families: those that handle FO requests, and those that handle BO requests.

(Figure 3: Core controllers)

(Figure 3: Core controllers)

As Figure 3 describes, there are currently several kinds of controllers:

- FO controllers – which handle FO requests

- Legacy controllers

- Native controllers (

FrontControllers) - Module controllers (

ModuleFrontControllers, based onFrontControllers)

- Native controllers (

- Legacy controllers

- BO controllers – which handle BO requests

- Legacy controllers

- Native controllers (

AdminControllers) - Module controllers (

ModuleAdminControllers, based onAdminControllers)

- Native controllers (

- Symfony controllers

- Framework controllers (

FrameworkBundleAdminControllers) - API controllers (

ApiControllers)

- Framework controllers (

- Legacy controllers

There are no controllers for Web services, since this system is mainly configuration-based and very tightly coupled to ObjectModel.

All legacy controllers are located in the — you guessed it — legacy stack, and use Smarty for templating. Symfony controllers, on the other hand, are located in the PrestaShopBundle and use Twig.

As the migration to Symfony progresses, legacy BO controllers are being migrated from the legacy stack to the PrestaShop Bundle stack. Once the BO migration is complete, there will no longer be any legacy controller in the BO.

Themes

There are two kinds of themes in PrestaShop:

- FO themes – of which you can have as many as you want, and are downloadable from the Addons Marketplace

- BO themes – which are not replaceable

Since FO themes work on top of legacy controllers, they are based on Smarty. They all integrate a shared core javascript library which is called “core.js”, which has jQuery 2.x bundled in.

In 1.7, PrestaShop introduced the parent-child theme feature, which allows themes to extend other themes. This feature makes it much easier to build custom themes.

PrestaShop comes bundled with a default FO theme, called “Classic”. Since the Classic evolves with PrestaShop, a great deal of community 1.7 themes are “children” of Classic, which allows them to inherit all the improvements that are added to Classic in every version, with minimal or no work required for their authors. Keep this detail in mind, we’ll discuss a major side effect of this in the next article.

Regarding BO themes, there are a couple subtleties to be aware of.

First, as explained before, BO themes are not interchangeable, but there are two of them nonetheless: default and new theme.

So why are there two? Well, legacy controllers are Smarty-based, while Symfony controllers are Twig-based. As a result, there’s a theme for each one: legacy controllers use the default theme, while Symfony ones use the new theme. As controllers are progressively being migrated to Symfony, templates are transformed from Smarty to Twig and moved from the default to the new theme.

In order to make things more interesting, the default theme is based on Bootstrap 3 and integrates jQuery 1.x, while the new theme is based on PrestaShop’s UI kit (available on GitHub), which itself is based on Bootstrap 4 and jQuery 3.x.

But there’s more.

Here’s what was said when announcing the architecture of 1.7:

Twig is Symfony’s templating language. In version 1.7, it will be used for all pages that are rewritten to use Symfony (Product page and Modules page), but NOT for the global interface (menu, header, etc.) nor the non-rewritten pages, which will still use Smarty. The two templating engines will be available, side by side, during the transition phase.

This means that the global interface is still being handled by the default theme, even in Symfony pages, which in part explains why Symfony pages may sometimes be slower than legacy ones (because they use both Twig and Smarty). The good news is that this is a temporary issue, which will get better when everything has been migrated to Twig and Symfony.

Finally, there’s Vue pages. Vue pages are hybrid: half-Symfony, half-API based BO pages. In those pages, the page’s skeleton is first rendered by a Symfony controller (therefore, based on the new theme), and then a VueJS application takes over in the browser and draws its content based on data sent by the BO API.

As stated before, currently only the Stock management and Translation pages are built on this technology. Even though we think that this is the way of the future (we’ll cover that in more detail later in this series), we find that going down this path in minor version releases would produce too many major extensibility and backwards incompatibility issues. Therefore, there will probably be no new Vue/BO API pages in 1.7.

Modules

The Modules system provides a plug-in approach to added functionality. As explained before, it relies mainly on specified extension points called “Hooks,” but their influence and deeply rooted relationships can go much further than that.

If you look at the Modules block at the center of Figure 1, you’ll notice that there are lots of arrows coming and going from it. Let’s explore these relationships.

Like we said, the main path for Module integration is Hooks, which are placed throughout the system. Modules can attach to them in order to provide or alter features.

There are two types of hooks:

- Display hooks – Integrated mainly (but not exclusively) in templates, they allow modules to inject content that will be displayed somewhere in a page.

- Action hooks – Allow modules to be informed of something happening in the system, and optionally alter the system’s behavior by modifying provided data.

The module system provides several other features:

- Module controllers – Modules can add new routes and custom pages in the FO or BO.

- Payment options – Payment modules can add payment options in the checkout process.

- Declaring and sharing services – Since 1.7.4, modules can use and declare Symfony services.

Modules can also be used to customize PrestaShop:

- Class override system – This system allows a module to replace any class in the Legacy stack.

- BO template overrides – Allows to replace templates from the new theme in the BO.

- Service overrides – Since 1.7.4, modules can replace Core services with their own.

- CSS and JS injection – Modules can also inject style and javascript code into a page.

In addition, modules can be customized by Themes. Themes supporting a given module can override the module’s own FO templates in order to improve their integration.

As you can see, the module system has many features, making modules very powerful. Modules have full access to the Core system, and even if modules submitted to the Addons Marketplace go through a quality and security review process, integration can go very deep into the Core. This power comes with a cost: the deeper the integration and customization, the more risk of upgrade and interoperability issues there is.

And more…

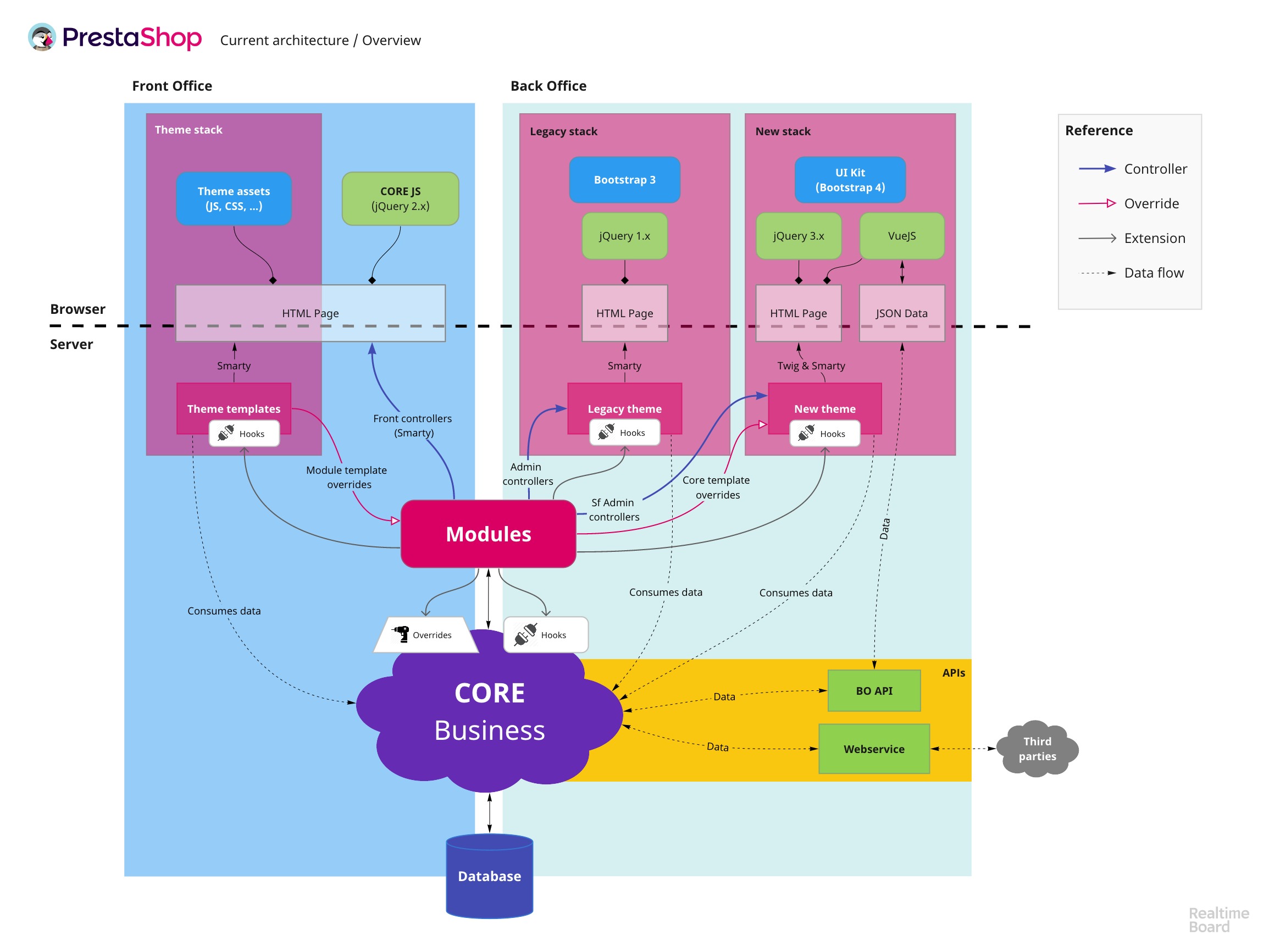

If you got here, now you know PrestaShop is much more complex than it can seem to be. Remember the overview at the top of the article? Take a look at this more detailed version of it now:

There are actually many more other subsystems than the ones we described, too many to cover them all in detail here. Just to name a few more:

- Translation and localization – PrestaShop can be translated and localized to any language and country: currencies, taxes, shipping locations, and more.

- Update – PrestaShop supports downloading and updating modules, and it can also update itself using the Autoupgrade module.

- Export/Import – Merchants can migrate their data from/to PrestaShop.

- Emails – All emails sent by PrestaShop are customizable and themeable.

That’s all for today! In the next part, we’ll analyze what are the main pain points of this architecture.

About the series

In case you forgot, here are the topics that will be covered during this series:

- The Current Architecture (or “Point A – Where we are”)

- Pain Points (or “What needs to be improved”)

- The Future Architecture (or “Point B – Where we are going”)

- Connecting the dots (or “Some ideas on how we’ll get there”)